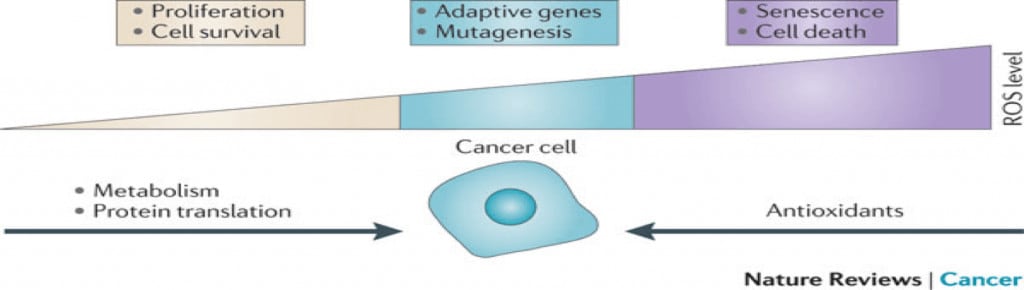

Although we have insufficient scientific arguments to sustain the fact that vitamin C administration improve cancer patients’ survival (Jacobs et al., 2015) – the idea that free radicals (reactive oxygen species = ROS) cause cancer is as popular as the idea that antioxidants are beneficial for cancer patients.

But the intracytoplasmic ROS level determines whether the cell progresses in the cell replication cycle or not, lower levels leading to cell cycle progression while higher ones leading to cell cycle arrest and cell death (Cairns, Harris and Mak, 2011).

Also, studies show that malignant cells have a higher tolerance for ROS than normal cells – Szatrowski and Nathan, 1991. So, to impede malignant cells survival and proliferation we need a higher level of intracytoplasmic ROS level.

And although vitamin C can act both as a pro-oxidant and antioxidant depending on the dosage, we do not know if the clinic impact of vitamin C administration is beneficial for patients with curable cancers during active oncology treatment and not during palliative care (Schumacker, 2006; Grasso et al., 2014).

Active oncology treatment with intention to cure makes the difference in what a cancer patient can or cannot take, and while there still are chances of healing antioxidants administration can decrease treatment efficacy.

Up to now, no randomised controlled trial has proven that vitamin C has a beneficial impact in cancer patients without metastasis during chemotherapy or radiotherapy done with intention to cure, the only benefits being increased quality of life and decreased palliative treatment toxicity in terminal cancer patients – Unlu et al., 2015; Li, Zhang and Tang, 2016

All studies showing antioxidants administration benefits are either case studies, animal studies, cell studies, studies done on incurable cancer patients or observational studies on cancer risk factors. Still the scientific interest is high, many researchers trying to prove that the improved quality of life or the decreased toxicity could be beneficial also for patients during active treatment and not only during palliation.

For instance, some researchers say cancer patients have vitamin C deficiency and therefore supplementing it would stimulate immune system and increase the quality of life of the patients, without separating either patients during active treatment from patients during palliation or the many types of cancer.

– But what cancer patients have vitamin C deficiency?

And although many naturopaths or complementary medicine practitioners would say “all”, the study that led to this popular assumption only analysed 50 terminal cancer patients of which only 15 had low vitamin C levels. Can we just delete the other 35 and extrapolate that “cancer patients have vitamin C deficiency”? – Maryland et al., 2005

The time of diagnosis is essential when it comes to antioxidants intake impact, and there are 3 distinct periods of time:

- before diagnosis – cancer prevention – when daily moderate intake of antioxidants naturally found in fruits, vegetables, raw seeds, legumes, lean meat, fish, whole dairy and eggs contributes up to a point to a decreased cancer risk

- early stage diagnosis – active oncology treatement with intention to cure – when oncology nutrition is strictly personalised based on malignant metabolism, tumour localisation, treatment stage and patient comorbidities. And I would like to underline that we cannot cure cancer through nutrition, be it oral or iv, and that during active oncology treatment the main goal is treatment efficacy and not decreased treatment toxicity or increased quality of life. During active treatment we have no proof that antioxidants have any beneficial impact on treatment efficacy.

- late stage diagnosis or when the disease has advanced and it reached an incurable stage – palliation – when the main goals are decreased treatment toxicity or increased quality of life. And this is the only period of time when antioxidants might be useful.

Some researchers go as far as to say that the only moment when cancer patients can be administrated antioxidants without decreasing healing chances is during scientific trials – Wilson et al., 2014

Even the chemotherapy with which vitamin C is compared by complementary / integrative medicine practitioners is palliative chemotherapy not curative active treatment. – Gourgou-Bourgade et al., 2012

Chemotherapy side effects are very popular and thickly underlined by these practitioners, but most don’t also mention alternative treatments side effects because their providers are not obliged by law to prove neither their efficacy nor their safety. And of course “they are natural thus they don’t have side effects”. Cocaine is also natural.

Malignant cellular biology is extremely complex. There is a huge difference between destroying some malignant cells in a Petri dish and destroying a self-born and grown tumour in a living organism.

To understand the difference between destroying some malignant cells in a Petri dish and destroying a self-born and grown tumour in a living organism imagine trying to destroy a wasp nest.

The fact that we catch some wasps in a jar and we kill them with substance X does not mean that the whole nest will be destroyed:

- the nest might have such a complex internal structure that some wasps might not come in contact with substance X, otherwise effective if contact would occur;

- the wasps we killed in the jar with substance X might be of different age or specie than the wasps in the nest;

- and some wasps might not be in the nest when we administered the substance, thus being able to go and build another nest elsewhere.

Cancer is a heterogenous mass of cells in different stages of cell cycle able not to die. And avoiding apoptosis is very complicated, involving a whole lot of genetic modifications that make malignant cells unpredictable and very adaptable.

Assuming that vitamin C is beneficial simply because it is an antioxidant or because it might act as a pro-oxidant sounds logic and natural, and low cost, and low importance because of the supposed lack of side effects, but up to now it is just a potentially risky assumption.

– Then why it is given intravenously in high doses in some centres even alongside neoadjuvant chemotherapy, treatment also widely practiced by many naturopaths or other integrative/complementary medicine practitioners?

Maybe because 40 years ago the Nobel laureate for chemistry Linus Pauling argued that high-dose vitamin C heals or prevents cancer, the same as 400 years ago the Pope used to say that the Earth was flat. So you should had been completely out of the box to even think it is round.

– What made Pauling sustain with such vehemence vitamin C for cancer treatment?

In the ’70 Pauling and Cameron published two apparently randomised controlled studies in which they managed to highly increase the survival of terminal cancer patients to whom they administered intravenously at first and orally thereafter high doses of vitamin C – Pauling and Cameron, 1976; Pauling and Cameron, 1978

But dr. William DeWys – the head of research at US National Cancer Institute at the time – has severely criticised the validity of these studies results (Cabanillas, 2010) because:

- the study has been restrospective and not randomised

- and because around 20% of the patients retrospectively selected to be included in the control arm died just few days after they have been considered incurable, dr. DeWys arguing that this led to an artificially increased survival time for the vitamin C group.

Then, in 1981, Murata et al. published a study with similar retrospective design – study widely quoted at the proof that Pauling and Cameron were actually right. – Murata, Morishige and Yamaguchi, 1981

But neither Pauling and Cameron’s studies nor Murata’s were randomised controlled trials, but restrospective ones without causal value. And what we also need to underline is that:

- all 3 studies were done on terminal cancer patients with diverse forms of cancer

- most patients died anyway within less than a year, so randomised or not, vitamin C for sure did not cure them

The hypothesis that curing cancer is as easy, simple and natural as vitamin C administration was later on contradicted by the very death of Pauling himself – who died of lung cancer in 1994 despite administering 18 g vitamin C daily. So in his case, taking vitamin C did not prevent cancer, and did not help him cure cancer after diagnosis.

Unlike these retrospective studies, the 2 randomised controlled studies done at Mayo Clinic showed that a daily oral administration of 10g of vitamin C is of no benefit for cancer patients – Creagan et al., 1979, Moertel et al., 1985.

But the results of these studies have been disputed based on vitamin C pharmacokinetics, vitamin C supporters arguing that the antitumor effect can be obtained only through intravenous administration. – Padayatty et al., 2004

But, even for intravenous administration there are at least 3 more but:

- despite the fact that the RDI for vitamin C is 60 mg, the supposed antitumor effect is not obtained even at doses as high as 70 g/m2 administred intravenously – Hoffer et al., 2008; Stephenson et al., 2013

- vitamin C administration can decrease oncology treatment efficacy:

- antioxidants can decrease chemotherapy and radiotherapy efficacy – Bairati et al., 2005; Lawenda et al., 2008; Heaney et al., 2008

- vitamin C inhibits the antitumor effect of bortezomib in patients with multiple myeloma or lymphoma – Perrone et al., 2009

- Vitamin C does have side effects – beside gastrointestinal discomfort (diarrhea, bloating) vitamin C administration can:

- increase iron absorption – being contraindicated in patients with hemochromatosis – Stotts and Bacon, 2017

- increase the risk of renal oxalates lithiasis in men – being contraindicated in patients with a history of oxalic nephropathy or renal insufficiency – Massey et al., 2005; Ferraro et al., 2016

- have a prothrombotic and procoagulant impact – being contraindicated in patients with cardiovascular disease at risk of thrombosis – Kim et al., 2015; Mohammed et al., 2017

Vitamin C is not as pink as pseudo-oncology industry would like patients to believe and the fight against cancer is far more complicated than simply taking vitamins.

In final stages, during palliative care, decreasing treatment toxicity and increasing quality of life are primary.

But during active oncology treatment for curable cancer we want the patient to feel good or we want the patient to be cured?

References

Unlu, A., Kirca, O., Ozdogan, M., & Nayır, E. (2015). Journal of Oncological Science.